The second generation of Protestant missionaries in China, as typified by James Legge, saw the Chinese Protestant church grow from one believer to over 80,000. Legge came from a prominent Scottish Congregational family, members of the same church as William Milne, Robert Morrison’s first co-worker. James did not become a Christian until 1836, but he was sent to China by the London Missionary Society only four years later, in the midst of the First Opium War. His shipmates included Milne’s son and Benjamin Hobson, who would later marry Morrison’s daughter Mary.

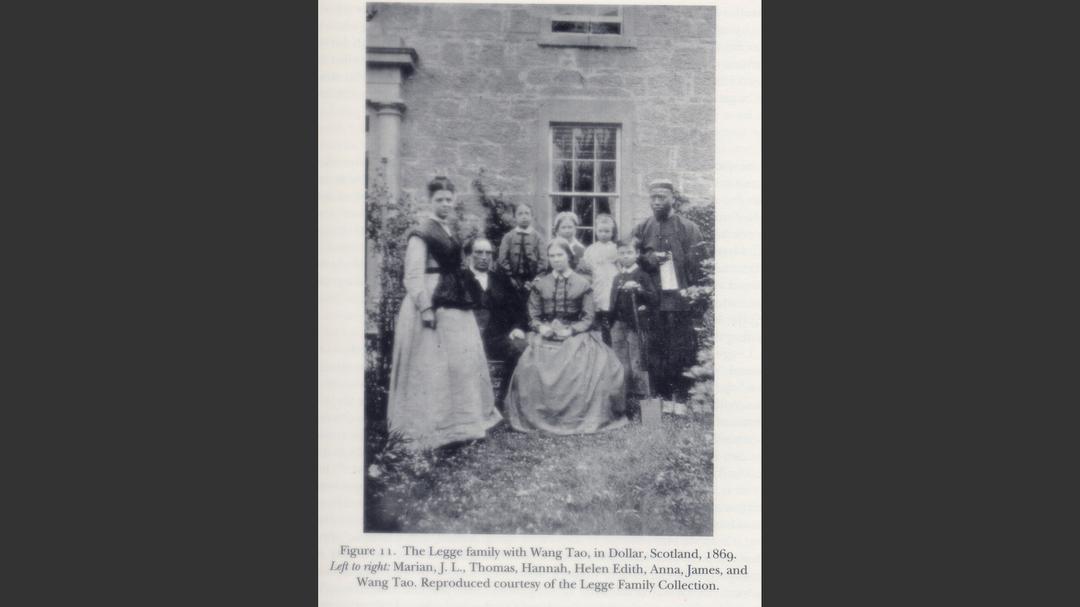

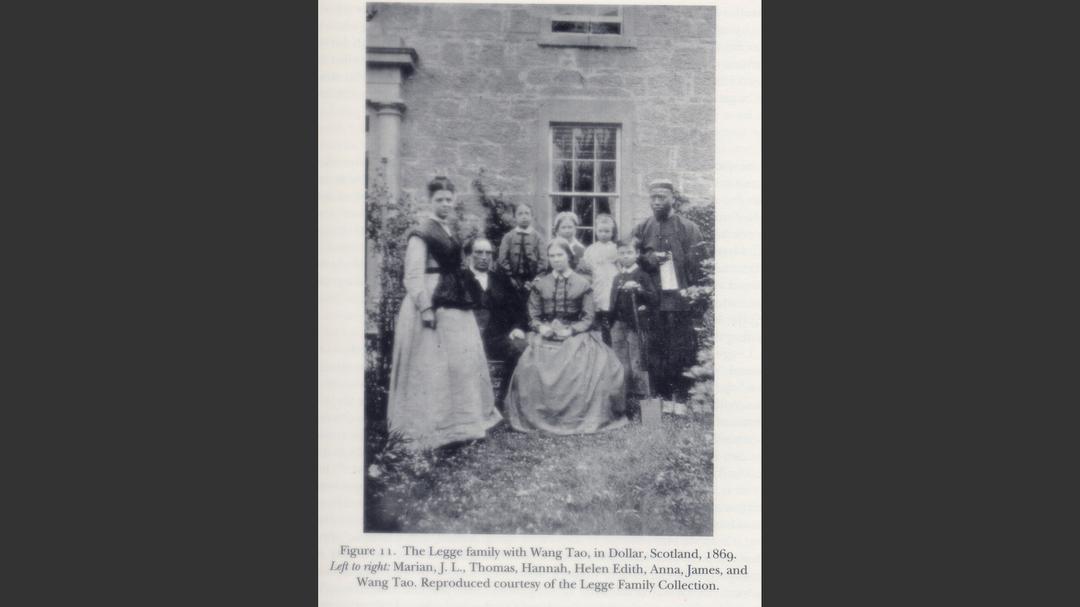

Legge played a key role in helping missionaries and other Westerners appreciate China’s cultural heritage. Working in Hong Kong for over three decades, Legge oversaw a seminary for Chinese Christians and pastored a church for the foreign community, but it is his work as a writer and translator that is best remembered. He worked alongside three notable Chinese Christians: Che Jinguang (车金光弟兄), He Jinshan (何进善牧师-Ho Tsun-sheen), and Wang Tao (王韬先生). Che Jinguang was baptized by Legge and became the first Chinese Protestant martyr when he was killed while serving at a mission station newly opened by Legge in Guangdong. He Jinshan served as Legge’s longtime co-pastor, and Lauren Pfister described him as “the first modern Chinese Protestant theologian well informed in biblical traditions…He set the pattern for the pastor-scholar among Protestant Chinese communities…” Wang Tao assisted Legge with his masterful five-volume Chinese Classics, work that convinced Legge that the ancient Chinese worshipped the God of the Bible.

When a controversy arose over which Chinese term to use for God in a new Bible translation, Legge wrote a lengthy defense of the term “Shangdi” (上帝-Lord on High). Legge left Hong Kong in 1873 to become the first Professor of Chinese Studies at Oxford. Before returning to England, he and a few fellow missionaries visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing. At that time, the emperor still offered annual sacrifices to Shangdi there. Before ascending the steps of the altar, Legge and others removed their shoes as an act of piety, then held hands and stood in a small circle to sing the Christian Doxology. Legge was criticized by some contemporaries as an “accommodationist,” but his scholarship has stood the test of time and has been complemented by later research into the Biblical roots of Chinese characters.

In 1839, just before moving to China, Legge married Mary Morison (no relation to Robert Morrison). She accompanied him to Hong Kong, bore him three daughters and took an active role in educating Chinese girls until her death at age 36. While on furlough in 1858, James married a widow, Hannah Mary Willetts (née Johnstone). They lived together in Hong Kong until poor health forced her to return to England in 1865. Legge joined her there from 1867-1870, and again after his retirement from missionary service. Mary died in 1881, and Legge continued to teach at Oxford and revise his translations until his death in 1897.

“Do the Chinese know the true God?”… I answer unhesitatingly in the affirmative. The evidence supplied by Chinese literature and history appears to me so strong that I find it difficult to conceive how anyone who has studied it can come to the opposite conclusion.

The Notions of the Chinese Concerning God and Spirits. James Legge. (Hong Kong, 1852), p. 7.