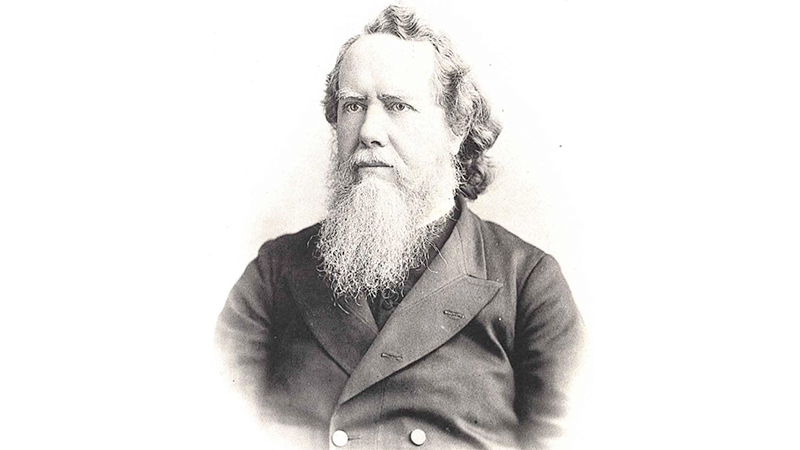

James Hudson Taylor was raised in a missions-loving home in England, and he came to Christ when he was 17. He left for China four years later, after painfully breaking off a courtship with a young woman who was not committed to missions. After six turbulent years in China, he returned to England. During his five years there God led him to found the China Inland Mission, with the aim of seeing the gospel preached as quickly as possible throughout China. Ralph Winter summed up Taylor’s preparation in these words, “With only trade school medicine, without any university experience, much less missiological training, and a checkered past in regard to his own individualistic behavior while he was on the field, he was merely one more of the weak things that God uses to confound the wise. Even his early anti-church planting missionary strategy was breathtakingly erroneous by today’s church-planting standards. Yet God strangely honored him because his gaze was fixed upon the world’s least-reached peoples.”

The CIM’s goal of rapid evangelization led to the adoption of several practices then unusual in China missions, including dressing Chinese-style, employing unaccompanied single females in remote posts, using workers from different denominations, no guaranteed salaries and no appeals for funds. Taylor believed that needs should be taken to God alone in prayer. The CIM byword was, “God’s work done in God’s way will never lack God’s support.” In the 1900 Boxer Uprising, the CIM lost more missionaries than any other agency, but before Taylor’s death in 1905 it had the most missionaries in China (825) and could claim 25,000 converts. A decade later, it was the largest missionary organization in the world.

Taylor’s emphasis on abiding in Christ emerges as one of his important legacies. When he was overwhelmed with a sense of failure and sin after over 15 years of missionary service, a co-worker sent him a letter of encouragement. It contained a description of what Taylor later called his “spiritual secret”: “To let my loving Savior work in me His will… abiding, not striving or struggling…A resting in the loved one entirely.” Through this insight into the abiding life, Taylor wrote that God had made him a new man.

Taylor married Maria Dyer in Ningbo in 1858, after a passionate courtship. Maria had been born to missionary parents in Malaya, and she shared Taylor’s commitment to evangelizing the lost. Hudson and Maria had eight children before her death in Zhenjiang, Jiangsu in 1870. In 1871 Taylor married Jennie Faulding, who had come to China with the CIM in 1866. Jennie helped raise Taylor’s four surviving children, along with three she bore and one daughter they adopted. Jennie’s ministry included leading a relief party of CIM women to Shanxi during the 1877-78 famine. She died in 1904, and Hudson died the following year in Changsha at age 73. Four of Hudson’s children became missionaries, and the family remains involved in China ministry to this day.

I am profoundly convinced that the opium traffic is doing more evil in China in a week than Missions are doing good in a year.

Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874-1917. Kathleen L. Lodwick (The University Press of Kentucky, 1995), p. 50.